By Jamie Scott

When it comes to determining priorities for teacher professional development, the decision-making process is generally driven by:

- The priorities or guidance of school leadership; or

- Teacher-directed choices.

Of course, there are several other factors and motivators influencing both parties in the decision-making process, such as:

- Statutory guidance or policy;

- Requirements specific to the type of role;

- Frameworks (e.g., Early Career Framework, Rosenshine’s Principles);

- Research evidence;

- Advice from colleagues and word-of-mouth recommendations;

- Career ambitions.

All the above (and more) can be valid and important. However, it seems there is a large student-sized gap here. No one has a bigger stake in the quality of teaching practices than students. Students are, after all, the intended beneficiaries of teaching practice – but can their experience convert to useful and reliable information to inform professional development priorities?

Do students know what’s good for them?

Is there anyone else who has more collective experience of the classroom environment and teaching practices than students? No. Peer observations and teachers’ own self-evaluations can be useful ways for teachers to prioritise and develop their practices. So too can gathering student perceptions. The idea of asking students about their experiences of school is not new. Many types of student surveys are in use already, providing insight relating to their attitude to school, their self at school or their wellbeing. Less common are student surveys that are focused on pedagogy.

Teaching is a complex and nuanced interaction among teachers, students, and content that no one tool can measure. However, there is already a good body of research that shows student surveys can provide valid indicators of the classroom environment and teaching practices (e.g., Marsh and Roche, 1997; Gates Foundation, 2012; Spooren et al., 2013). The Gates-funded MET project identified student surveys as one of three ways of reliably measuring teaching effectiveness, producing more consistent results than classroom observations. When asked the right questions, in the right way, student perceptions can be harnessed to offer an important source of information on pedagogical practices and the classroom environment. In turn, the feedback they generate can be a powerful tool for teacher learning – offering additional insight that allows teachers and leaders to personalise professional development.

If we want students to learn more, teachers must become students of their own teaching. They need to see their own teaching in a new light.”

Tom Kane, Professor of Education and Economics at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and leader of the MET project

Feedback for Great Teaching

While acknowledging their limitations, we felt there was sufficient evidence for the potential validity of student surveys to create our own for inclusion as part of the Great Teaching Toolkit. Furthermore, it was impossible to ignore the impressions and perceptions of the biggest stakeholder in teaching effectiveness – those who have spent the most amount of time with a teacher in school. So, during the aca(pan)demic year of 2020/21, Professor Rob Coe and the team at Evidence Based Education developed student surveys in each of the four dimensions from our Model for Great Teaching:

- Understanding the content

- Creating a supportive environment

- Maximising opportunity to learn

- Activating hard thinking

The surveys were trialled by teachers and students in schools spread around the world, enabling a cycle of data collection, statistical analysis, and question development. Following a nine-month process and over 1,500 student responses later, in September 2021 we released version one of the student surveys for use in schools.

An example can illustrate. One of the statements in the pilot survey is “Sometimes it is loud and chaotic in this class”. Students are asked to select from Agree Strongly to Disagree Strongly on a five-point scale. In most cases we would want students to disagree with this statement, since being loud and chaotic is not generally associated with efficient learning. So, we were quite surprised to find that the overall proportion who disagreed or disagreed strongly was only 12%. For some teachers, no students in their class disagreed; for others, as many as half did.

Each teacher who gives the survey to their class gets confidential feedback that shows the proportion of their students who gave a ‘desirable’ response to each survey item. Of course, there may be many reasons why students perceive a class as loud and chaotic, so it is not necessarily a bad thing, but we also provide the overall average as a reference point. The feedback from the survey is intended to provide insight and information, holding a mirror up to your classroom, not making a judgement. In the pilot, many teachers said they found this insight into their students’ perception interesting – sometimes challenging or surprising, but informative and useful.

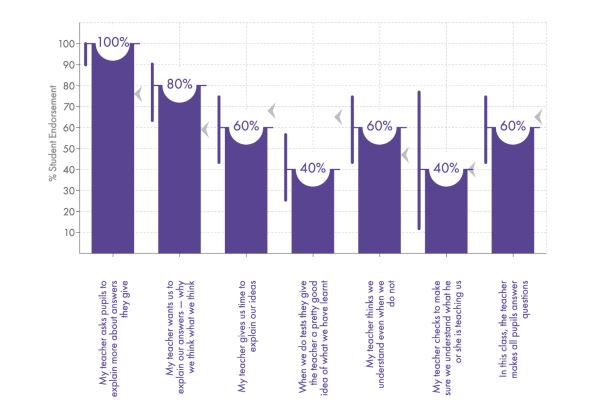

The image below is an example of feedback from a student survey relating specifically to Element 4.3 (Questioning) of the Model for Great Teaching. It shows the proportion of student endorsement for each statement. A grey arrowhead points to the mean percentage endorsement for all students who have completed the survey, from all teachers and schools in our sample, for comparison.

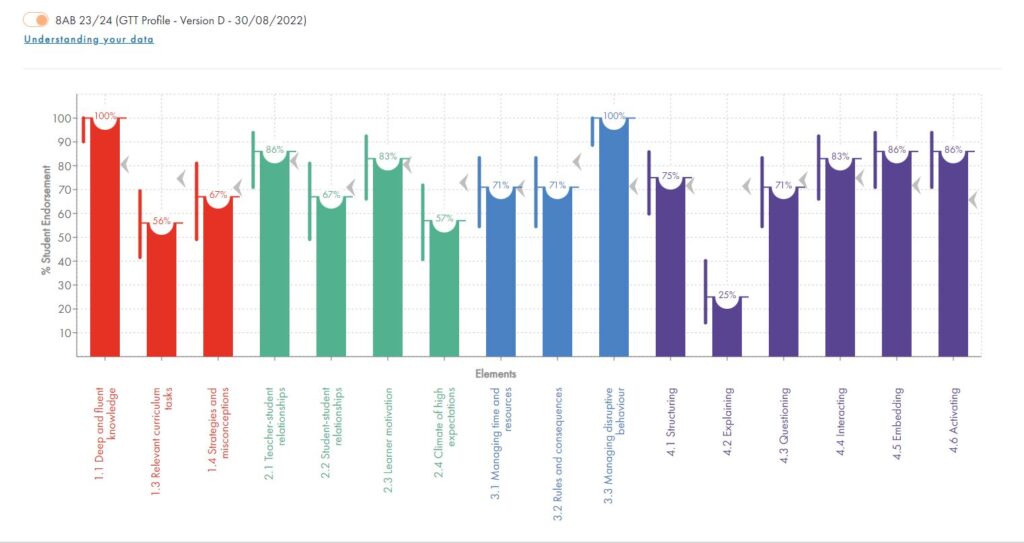

The next image is an example of feedback from a student survey relating to all four dimensions of the Model for Great Teaching. It shows the proportion of student endorsement for the elements.

For the avoidance of doubt, on no level are we attempting to reduce the complex art of teaching to a number. Nor are we seeking the biased likes and dislikes of students on how their teacher goes about their job. Feedback is confidential to the teacher, accessed through their own private account. What is being explored is level of agreement from students as to whether certain things are happening in the classroom. The strong, overarching goal here is to provide additional information to the teacher to help inform their professional learning.

As such, we’re delighted to offer individual teachers free access to the Great Teaching Toolkit: Student Surveys. Click here to create your free account. Once you have created your account, you will be able to use the surveys to:

- Answer the question ‘What can I best focus on to improve that will optimise student learning?’

- Make evidence-based, personalised decisions about how to use precious time for professional development.

- Generate insights to better understand classroom climate.

- Give students a voice in teaching and learning.

- Contribute to active and ongoing research.

Can student surveys provide useful feedback to teachers? There is good evidence to suggest that they can – and we’re about to contribute more to that body of evidence.

Find out more about the Great Teaching Toolkit here.

What next?

What next?

Your next steps in becoming a Great Teaching school